Cards on the table, I’m a fan of the administrative state. Societies are large and complex, and a little technocratic competence goes a long way in ensuring the availability of public goods and infrastructure. But there are some areas where the administrative state struggles. Sex, for one.

Or, more accurately, fertility. I’ve been thinking about this because a couple of weeks ago the New York Times Asian fertility desk1 was on fire. Over a few days they published stories on Chinese local officials pushing families to have more children, on Japan’s thirty-year struggle to raise its birth rate, and on South Koreans compensating for lack of children with pets.

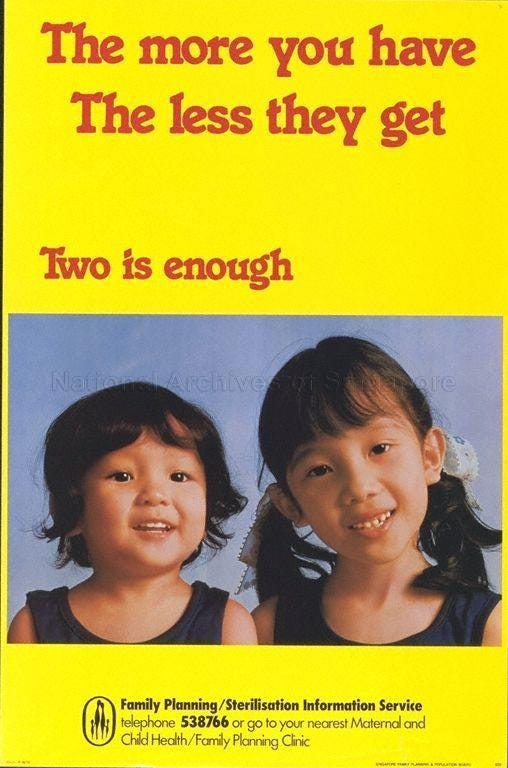

Like China, my adopted home of Singapore advocated for limited birthrates during the 1970s “population bomb” panic, when it was widely agreed we were destined to devour each other like starving jackals. Singapore realized its demographic error in the 1980s, as its birthrate plummeted, and went through policy whiplash. When I arrived, in 1995, there was an advertising campaign encouraging young couples to have larger families. I recall lots of slow-motion video and gauzy photos of attractive young couples with cherubic babies, and an omnipresent theme song. Alas, it was too early to be immortalized on the Internet, but there is evidence of later campaigns.

Why are governments so preoccupied with nudging fertility rates up? Two words: demographic decline! If the fertility rate is low, populations, and especially workforces, age and eventually shrink. There are fewer working-age adults to contribute to the tax base, prop up the pension funds, look after the grandparents, serve in the military, and so on. Extrapolate the line far enough and, well, it’s not good for real estate, which is the major preoccupation the planet.

Economic development correlates remorselessly with decreasing birthrates, regardless of government incentives. At 1.1, Singapore’s fertility rate remains about half of replacement, ahead of only South Korea and Hong Kong and just 0.1 behind mainland China. The US does relatively well at 1.7, but that’s still well below replacement, reported as anywhere from 2.1 to 2.3 surviving children per woman, depending on the source.2

It pains me to report that I am the aging workforce. I turned 57 earlier this month, and no one is more surprised about it than I am. But neither the numbers nor thermodynamics (manifest in the vortex of entropy in my lower back) lie. Delightfully, I live and work in Silicon Valley, which has a cult of youth second only to Hollywood. I’ve visited company campuses that felt like the domed city from Logan’s Run, where everyone is young and sleekly beautiful because anyone over 30 has been sent to Carousel for “renewal.”(Read: death.)

I and my wife have failed in our demographic duty. We have only one child to replace the two of us, and have therefore dragged down the averages of both the US and Singapore. In a few years he’ll have to choose his citizenship and one country or the other will get zeroed out. We made the mistake of starting late. I was 37 and my wife was 32 when we started trying to have a child in earnest. That was the first time I felt prosperous and stable enough to be a parent.

In my defense, Generation-X absorbed a lot of neuroses growing up. Many of us were children of divorce. My own parents were in their early 20s when I was born, and about 30 when they split up, painfully. We then came of age during the AIDS pandemic, when the posters covering the walls of our dorm bathrooms assured us that careless sex would straight-up kill us. It was a lot to process. How can a pro-natal bus stop poster compete with marrow-deep generational angst?

Also, our ‘80s sex-ed classes were big on all the things that could lead to pregnancy when we were young, and skipped over the part where the human fertility curve plunges through the X axis and into negative territory in a vertical line after age 30. It took years and a significant amount of engineering to arrive at our son. So much temperature taking and charting and spreadsheets and unromantically scheduled sex. No one cares if you’re not in the mood, comrade, buck up and do it for the motherland!

Despite our poor showing, my wife and I are direct beneficiaries of Singaporean pro-natal policy. When our son was finally born we registered him as a Singapore citizen and the government gave us a “baby bonus” of SGD$7,000. (And a gift basket, possibly because I nagged them online about his passport.) We also registered our son as a US citizen, but the United States government did not send us a check. Cheap bastards, rolling in their 1.7 fertility rate largesse.

There would have been a bigger bonus for a second child, but we never managed it. We were living in the US by then and gave up after months of fertility injections and running the eye-watering numbers on IVF, which the American health insurance industry refuses to subsidize because they are feckless traitors heedless of the national welfare. So we have our singleton son and two cats. Regrettably, no matter how much we treat them like weird little people, cats will never contribute to the tax base or public welfare.

The baby bonus was nice, but it had nothing to do with our choice to have a child. Decisions about having children are deeply personal and complicated and it’s difficult to change course on national fertility, even in states with famously good social support services. No amount of national pro-natal campaigning was going to change the outcome for our family.

But I still find pro-natal campaigns fascinating as communication exercises. Does it work to exhort people to have more children for the security and prosperity of the state? Probably not. Some campaigns focus on children as security for your old age, especially in China. But “breed more or die alone in an alley” only goes so far as a core message, even if you put it in curly font over a photo of a beaming cherub. Sensibly, most campaigns focus on abundant children as a path to personal fulfillment. Like mastering a language or renovating your kitchen.

In keeping with American political doctrine, our own pro-natal campaigns are largely privatized. This has led to a weird combination of VC techno-optimization and volkish neo-agrarian fantasy. In Silicon Valley, the galaxy-brain solution to demographic decline appears to be a combination of weird anti-aging hacks and the Singularity. Will immortal man-gods drunk on infusions of teenager plasma want to spend their eternal lives tending to the servers that support uploaded consciousnesses in the Metaverse? Sounds like something Neal Stephenson dreamed up after a night of molly and plastic-bottle schnapps.

Anyway, back on planet Earth, the state usually takes the lead in pro-natal campaigns. I am super curious about the tension between conservative government bureaucracies and the grubby, mucus-coated business of actually making babies. Somewhere between the state-organized mixers and the dreamy three-child rambles through serene and well lit parks, someone has to get busy. Imagine the meetings!

Minister: “We need to schedule mixers for young people to encourage them to marry and have babies.”

Aide: “Excellent, sir. We’ll set up a bar, serve some drinks and…”

Minister: “What? No! No alcohol! We don’t want to encourage vice.”

Aide: “Understood. Perhaps music and some dancing to get people in the mood.”

Minister: “Nothing with too much of a beat.” [Drops thick report on desk with a thud.] “Did you know the Ministry of Health has determined the pelvis to be the most salacious of bones?”

Aide: …

Minister: …

Aide: “So, bottled tea and Kenny G?”

Minister [tracing lines on a complicated chart]: “Low risk of twerking. Approved. I am confident this program will drive a measurable increase in breeding stock, soldiers and units of economic productivity.”

Aide: “You mean kids?”

Minister: “Sure. That, too.”

I suppose there’s always immigration. Seems un-controversial, right?

Not a thing, but it might just as well have been.

My mom, an actual demographer, could probably explain why it’s expressed per woman, but I assume it’s because women are the constraint due to pregnancy and childbirth and men are, well, men.